SERHIY ZHADAN

Serhiy Zhadan was born in Starobilsk, Luhansk oblast, in 1974. He is a Ukrainian poet, fiction writer, essayist, and translator. He has published over two dozen books, including the poetry collections Psychedelic Stories of Fighting and Other Bullshit (2000), Ballads of the War and Reconstruction (2000), The History of Culture at the Beginning of the Century (2003), Lili Marlen (2009), and Life of Maria (2016). His novels and collections of short stories include Big Mac (2003), Anarchy in the UKR (2005), Anthem of Democratic Youth (2006), and Mesopotamia (2014). The English translations of Zhadan’s work include Depeche Mode (Glagoslav Publications, 2013), Voroshilovgrad (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016) and Life of Maria and Other Poems (forthcoming with Yale University Press in 2017). Other translations of his work appear in PEN Atlas, Eleven Eleven, Mad Hatters Review, Absinthe, International Poetry Review, and the anthologies New European Poets (2008) and Best European Fiction (2010). In 2014, he received the Ukrainian BBC’s Book of the Decade Award, and he won the BBC Ukrainian Service Book of the Year Award in 2006 and again in 2010. He is the recipient of the Hubert Burda Prize for Young Poets (Austria, 2006), the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature (Switzerland, 2014), and the Angelus Central European Literature Award (Poland, 2015). Zhadan lives in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

POEMS

Three years now we’ve been talking about the war. . .

So that’s what their family is like now. . .

Sun, terrace, lots of green. . .

The Street. A Woman Zigzags The Street. . .

Village street – gas line’s broken. . .

At least now, my friend says. . .

Thirty-Two Days Without Alcohol

From the Translators

Amelia Glaser & Yuliya Ilchuk

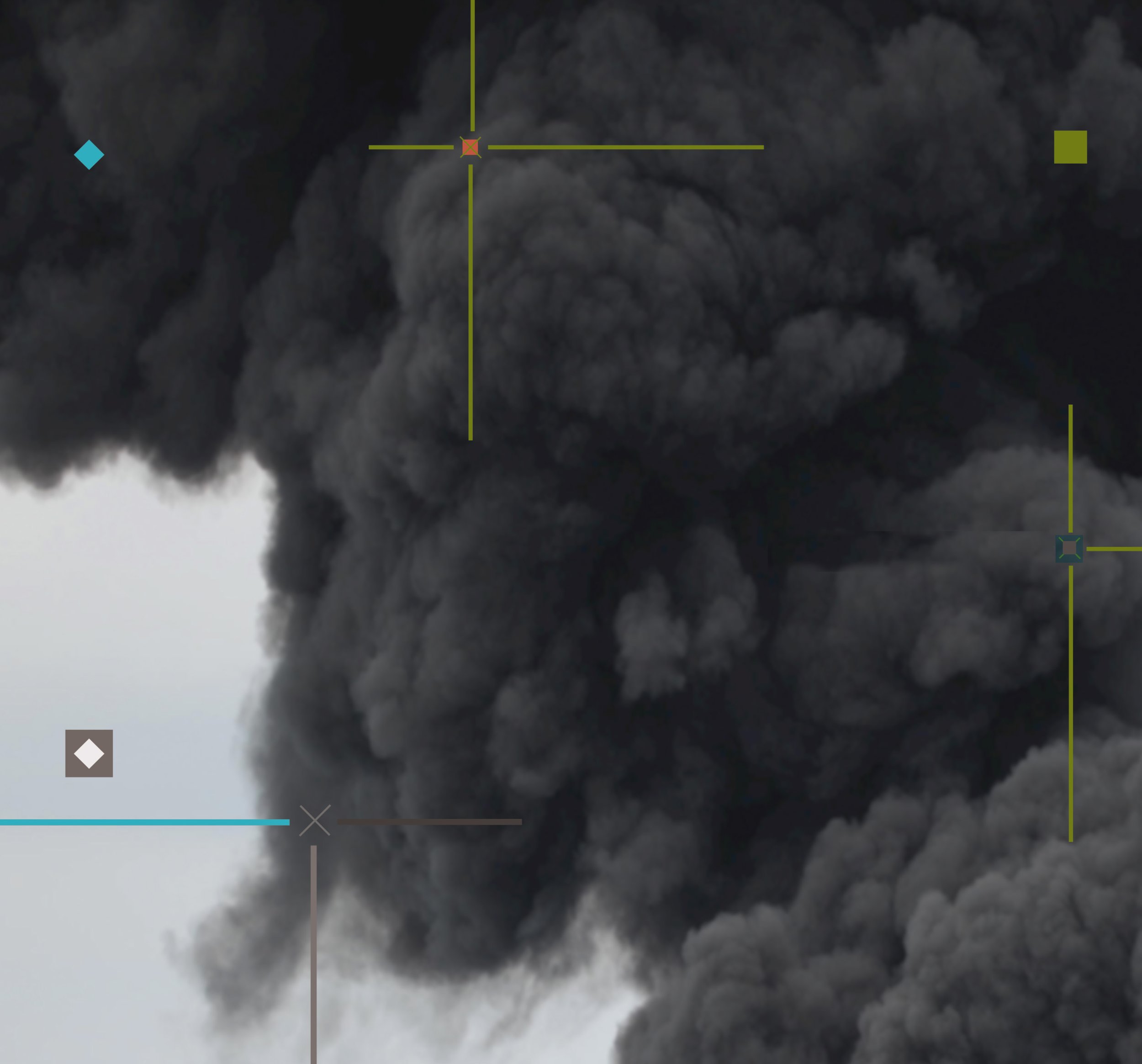

Serhiy Zhadan, an internationally acclaimed poet and novelist – oh, and front-man for the popular ska-band “Dogs in Space” -- has put his art to the service of Ukraine’s war-torn Donbas border region. Born in 1974, Zhadan studied and taught Ukrainian and world literature at the University of Kharkiv until his “retirement” from teaching in 2004 to focus solely on his writing. The author of over a dozen collections of poetry, five novels, and several collections of short stories, Zhadan, whose first books of poetry appeared in the 1990s, more recently has become known as a civic poet and public intellectual committed to developing an inclusive society in Ukraine. A native of Eastern Ukraine, Serhiy Zhadan was active in the Kharkiv protests in 2014 -- he was badly beaten while peacefully demonstrating. He has since worked to provide humanitarian aid and working toward peace in the zone of military conflict, cofounding, in February 2017, the Serhiy Zhadan Charitable Foundation, which assists communities in the Donbas. In his collections published since the war broke out -- Life of Maria (2015) and Tamplers (2016) -- the poet presents the conflict in a series of meditations with hints of the religious in both content and form. In Zhadan’s vision, Ukraine, like many other countries in Europe, has entered its own version of Middle Ages, i.e. a long-lasting war for an idea that consumes those on both sides of the front-line.

Zhadan’s recent cycles of poetry incorporate conversations with individuals the poet has met in Donbas, but some of these types -- the Protestant missionary, the hardened “bro”, the drunk -- will be familiar to readers of his pre-War works. Zhadan’s poetry is at once specific to Eastern Ukraine and highly translatable. His line is spare – avoiding excess pathos and striking a balance between the serious and the sentimental. “Headphones” channels Sasha – a lonely figure navigating a lonelier world, a figure who, in spite of it all, manages to preserve humanity and even art. “Rhinoceros” compares the exotic concept of death to an exotic animal at the zoo. The title suggests the characters from Ionescu’s “Rhinoceros” who, falling prey to the reigning ideology, become wild beasts. Zhadan has an ear for the colloquial and the rhythmic. The candid, factual lines that open “Needle” yield to the more sensuous repetition of “B’esh, b’esh, tatuiuval’niku” (Carve, carve, tattoo-artist). Zhadan will sacrifice slang and romance alike for hard-hitting truth. In “Needle,” the tattoo artist who “exists to fill the world with meaning,” is taken out in the most meaningless of places – at a roadblock. But the final lines of the poem deliver the harshest blow. Is this, the Donbas war, the stuff of heroic poems? Perhaps. Or perhaps, instead, the incident will be forgotten. That is to say, this poem, without ever calling the events in Donbas a "war," is also a poem about what war means, and about how individuals living through war or peace, leave their marks on the world.