BORIS KHERSONSKY

Boris Khersonsky was born in Chernivtsi in 1950. He studied medicine in Ivano-Frankivsk and Odessa. He initially worked as a neurologist, before becoming a psychologist and psychiatrist at the Odessa regional psychiatric hospital. In 1996 Khersonsky took on an appointment at the department of psychology at Odessa National University, before becoming chair of the department of clinical psychology in 1999. In the Soviet times, Khersonsky was part of the Samizdat movement, which disseminated alternative, nonconformist literature through unofficial channels. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Khersonsky came out with seventeen collections of poetry and essays in Russian, and most recently, in Ukrainian. Widely regarded as one of Ukraine’s most prominent Russian-language poets, Khersonsky was the poet laureate of the Kyiv Laurels Poetry Festival (2008) and the recipient of the Brodsky Stipend (2008), the Jury Special Prize at the Literaris Festival for East European Literature (2010), and the Russian Prize (2011).

POEMS

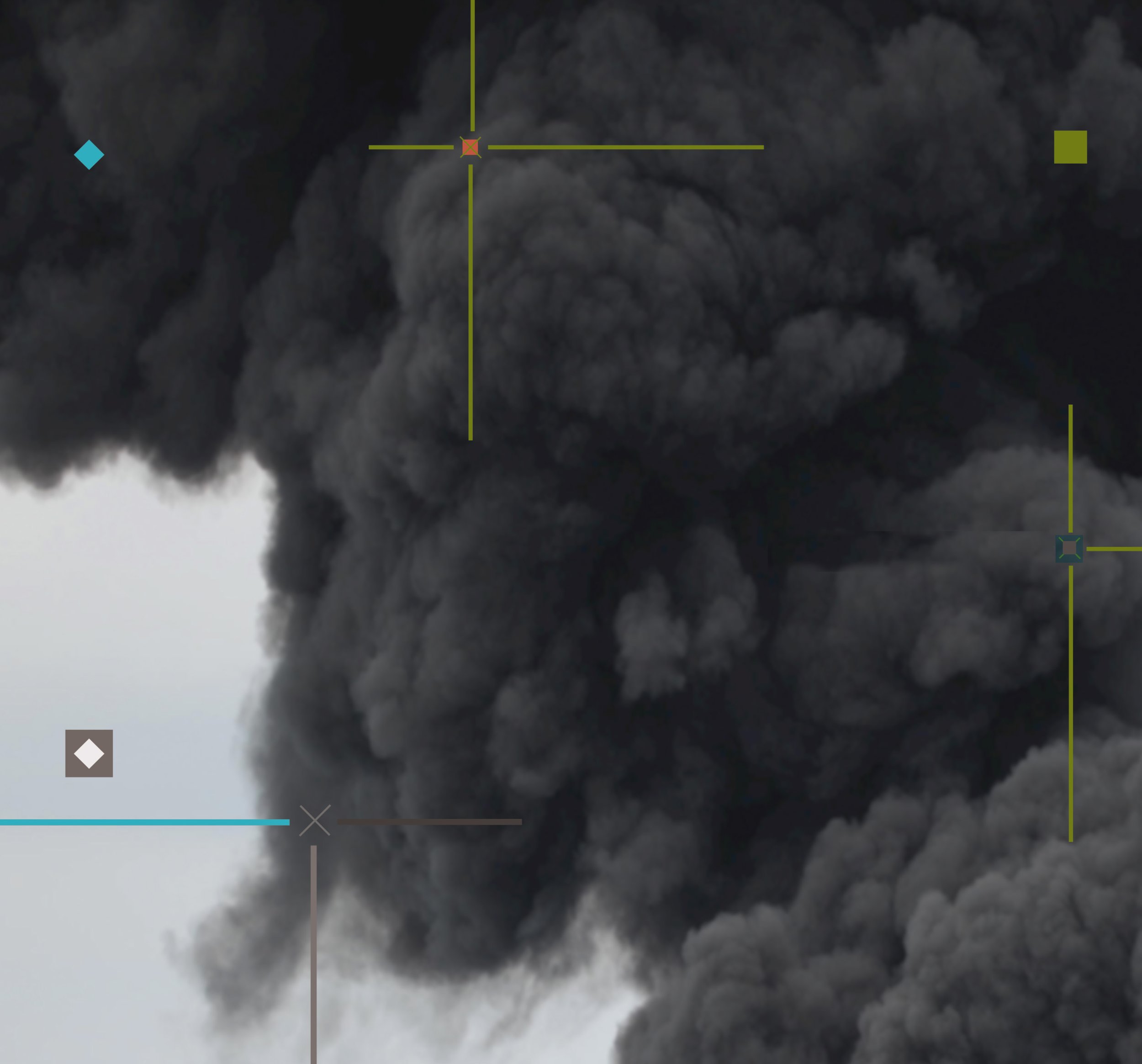

explosions are the new normal. . .

all for the battlefront which doesn’t really exist. . .

people carry explosives around the city. . .

way too long the artillery. . .

when wars are over we just collapse. . .

modern warfare is too large for the streets. . .

From the Translator

Olga Livshin

To readers interested in understanding the psychology of a certain kind of post-Soviet Russian thinking that contributes to the war in Ukraine, Boris Khersonsky’s work is indispensable. It frames the war within the larger context of millennia-old imperial ambition and the myopic patriotism of empire’s citizens, and it treats these destructive phenomena with urgency.

To accomplish this, Khersonsky borrows certain elements from Joseph Brodsky’s seminal work. Like Brodsky, he avoids open emotional expression; both poets place irony like a cement block in the place where the rainbow-hued Soviet confessional poetry of the 1960s used to be. Khersonsky also mines Brodsky’s work for the existential emptiness and dejection that underlie many of his poems. Most importantly, he continues Brodsky’s reflection on empire as a nauseating phenomenon that recurs ad infinitum. Yet whereas Brodsky expresses an ironic resignation towards empire, characteristic for late-Soviet nonconformist culture, Khersonsky’s poetry bristles with resistance. An outspoken opponent of the war on many occasions in public appearances and on social media, in his poetry he deploys parody, turgid with anger.

In one poem, Khersonsky parodies a male speaker who cannot imagine himself apart from the jingoistic, ultra-masculine identity that had been handed to him by “warrior ancestors and Lenin’s words/ and his commandments and soaring iron birds.” Irony pushes the boundaries of logic to expose the costs of violent imperial conquest. Imperial glory is the speaker’s only possible glory; ongoing war, the only way to keep the adrenaline of glory pumping. The speaker is impotent in any other scenario—so much so as to fantasize about the murder of his family members.

Khersonsky’s peculiar pacifism forms a foundation for his resistance of empire. The “I” of one poem talks of bodies and homes as ineffably exposed and fragile, as in this poem about the terrorist attacks in Odesa: “an enemy chooses weapons as a thief finds the pick for a door / when in fact the door was already open.” What is the source of this protest for wars by empire—quaint and associated with Tolstoyanism, conscientious objectors, or waves of revolutionary ideas about transforming the world? Khersonsky insists that even if the Soviet project failed, its legacy continue to pile on horrors. His poetry embodies the Soviet imagery that glorifies war and the esthetic of war—“my beloved rifle, we’ve reached the end of our shining path”; and it inhabits, with tight-lipped anger, the Soviet rhetoric of modern, rational, purportedly scientific war strategy: “[M]odern warfare is too large for the streets —/ a problem solved by a thousand-pound bomb.” Exploding these images, he underscores that history repeats itself; no one does much about it. No one—except the poem, which is doing the important work of watching and waking up the reader.

Khersonsky’s focus in doing this work rests not only on the victims on one side: ultimately, war itself is imagined as helpless and exposed, “…a little girl, hair tied in a bow—she can barely walk on her own.” This is not pacifism of calling for action, but, rather, of bearing witness and rousing outrage even as the ongoing reality of war, its constant news stream, makes one numb.