YURI IZDRYK

Yuri Izdryk was born in Kalush, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, in 1962. He is a poet, novelist, and literary critic from Kalush. In 1986, Izdryk was deployed to the site of the Chernobyl disaster to help clean up the radioactive waste. Since 1990, he has worked as the editor in chief of the avant-garde literary journal Chetver. A prominent figure in Ukrainian alternative literature and culture, Izdryk is the author of four novels in Ukrainian: The Island of Krk and Other Stories (1993), Wozzeck (1997), Double Leon (2000), and AM™ (2004). The English translation of Wozzeck appeared in 2006.

Yuri Izdryk Was and Is Many Things

Marko Pavlyshyn, Monash University

Yuri Izdryk was and is many things: a master provocateur and deconstructor of contemporary literature and art in Ukraine; an author of prose phantasmagorias that yet contrive to paint terrifyingly persuasive pictures of human anguish and desolation; a consummate stylist in the many genres – short novel and short story, poetry, essay, music, graphic art – in which he is as much experimenter as adept; initiator and editor of the avant-garde journal Chetver (Thursday, 1989-2008); and core member and quintessential representative of the “Stanislav phenomenon,” a movement named after the west Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivs’k (earlier Stanislav or Stanislaviv) and characterised by its refusal of the dominant realistic and engagée traditions of Ukrainian high culture. And yet, despite what Izdryk’s friend and fellow exponent of the Stanislav phenomenon Yuri Anrdrukhovych ironically labelled his “(pardon the expression) ‘postmodernism,’” one may descry through Izdryk’s formal pyrotechnics and his often scandalous content a minimal, but consistent core of values and beliefs. These, vividly on display in the two poems included in this anthology, are commitment to an ethics grounded, despite reservations and doubts, in faith in a Christian God (in the essay “Yearning for the Unreal [1995] Izdryk memorably classified himself as a “believing mammal”); and a no less circumscribed and uncertain devotion to the interpersonal love that can ennoble and reconsecrate human experience.

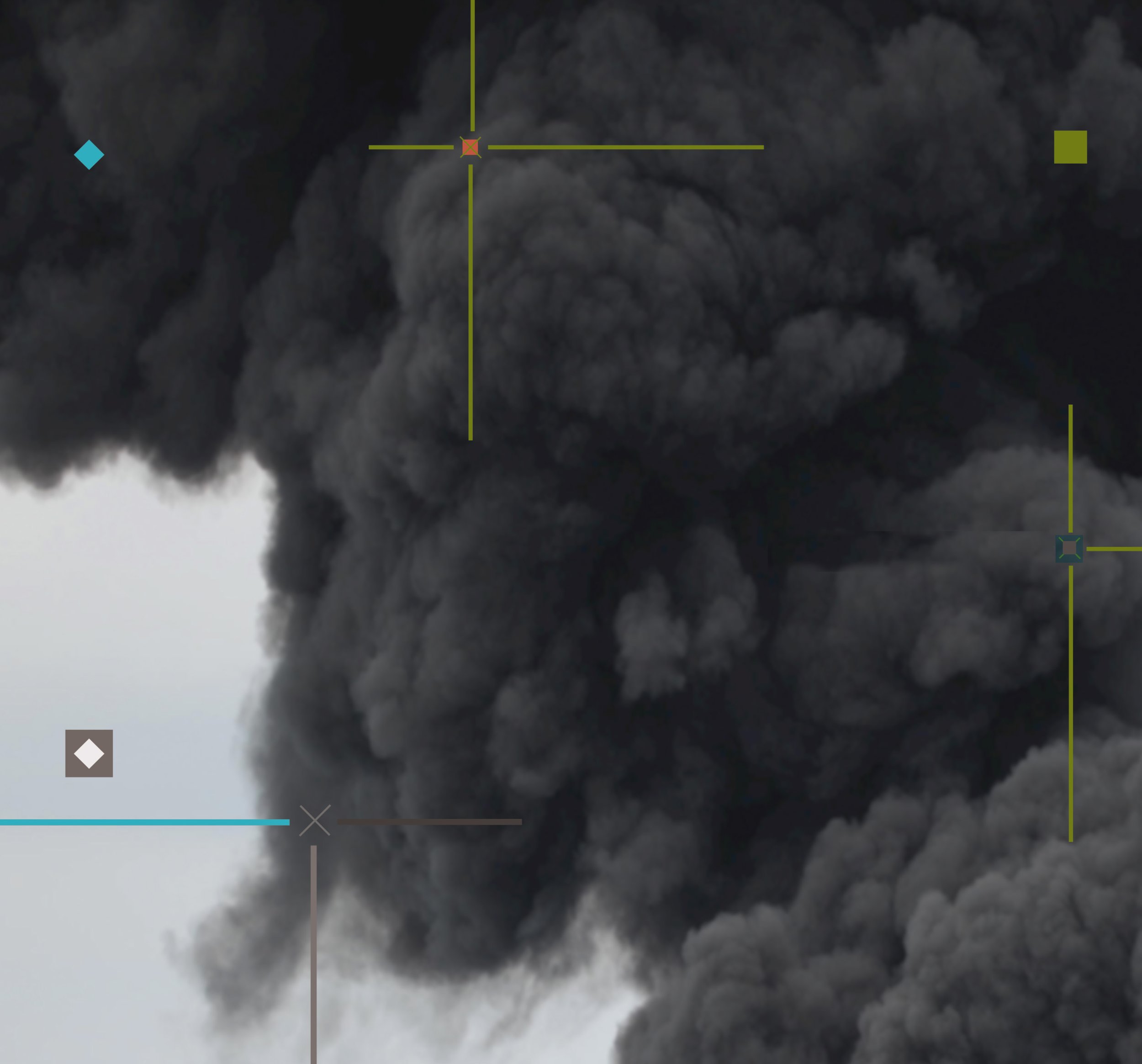

In “Darkness Invisible” the world presents itself as saturated with evil – not an active force, but an omnipresent temptation enticing the individual to choose sin. The instance of such choice singled out in the poem is the decision to follow the drum of war (in Izdryk’s original the “tin drum” – one of his characteristic allusions to other texts, here the novel by Günter Grass). And yet the sense that two people can share of being together engenders faith in the power of (human) love, a correlate of (divine) mercy. The concluding sunburst of hope comes as a last-minute reprieve after five heavy stanzas of stony hexameters capped with relentless masculine rhymes – an architecture of portent that Boris Dralyuk’s translation has chosen to exchange for a lighter structure where image eclipses rhythm as the main carrier of sense and mood.

“Make Love” is even more direct in its refusal of war, alluding in the very title (as in “Darkness Invisible,” the original title is in English) to the 1960s countercultural slogan “Make Love Not War,” and in the poem’s first line to the Sixth Commandment. In the context of a real defensive war in Ukraine’s East, a war which might well meet theological criteria for a “just war,” the poem’s lyrical subject, boldly abjuring patriotic justifications, pronounces war to be, not merely an opportunity to live the injunction “thou shalt not kill,” but a challenge to “protect one another” – a wartime paraphrase of the Gospel injunction, “Love one another.” The two poems are as direct and disarming – in both senses of that word – as Izdryk’s discourse, elsewhere often opaque, can be.